14/02/2022 Vietnam

“If you ever come across anything suspicious like this item, please do not pick it up, contact your local law enforcement agency for assistance”

Wars transform nations. Then they end, and as their veterans die, they fade from living memory into history. That is now happening to the Vietnam War, the conflict that dominated both America’s foreign policy and its domestic politics for much of the 1960s and 70s.

Half a million Vietnam vets left

By one estimate, around 610,000 Vietnam veterans were still alive in 2019, out of a total of 2.7 million who served. With an average historical attrition rate of about 44,000 per year, that would put the number of U.S. vets of the war in Southeast Asia currently alive around half a million — fewer than one in five of the original total. For most other Americans, “Vietnam” is ancient history. Heck, even Rambo is 40 years old. The nearest intimation anybody under 50 has of what the war must have felt like, came last year, with the chaotic U.S. evacuation of Kabul. As some with long memories said, it was so eerily reminiscent of the Fall of Saigon in 1975. But mostly, the Vietnam War has fallen off the radar. Perhaps, this is not so surprising. The martial appetite of those vast legions of armchair generals is sated by an endless stream of content about World War II. As for Vietnam: Communism, which Americans went there to stop from spreading, is no longer a geopolitical threat. Vietnam itself is now an exotic holiday destination for Americans, even a potential ally against China. Yet there are still doors in time that open directly from here and now into the horror of what the Vietnamese call “the American War.” Pictures, mainly — of that Buddhist monk, self-immolating in anti-war protest, or of that girl, naked and crying because of the napalm that flattened her village and burned her skin.

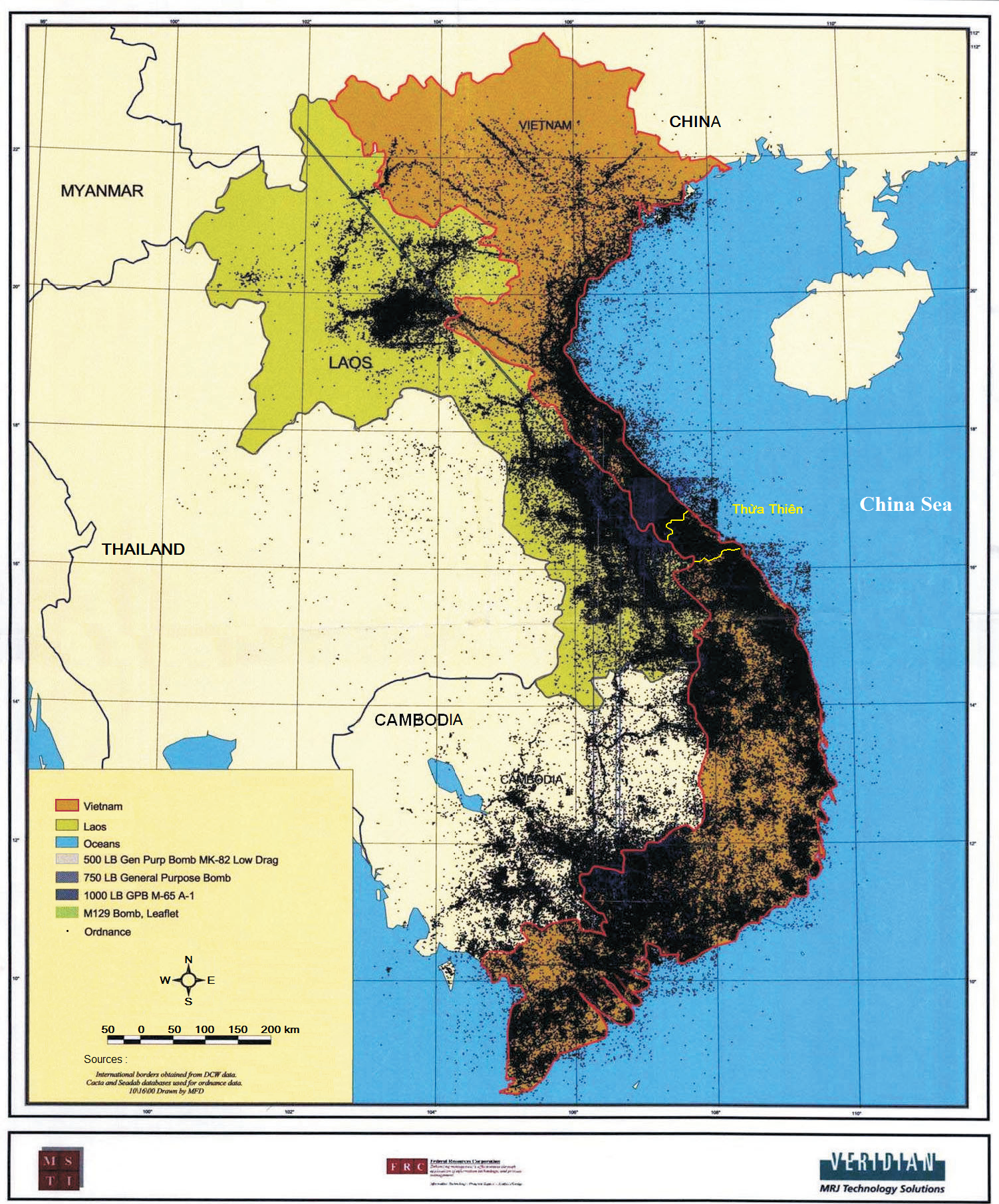

A carpet bombing map of Vietnam

But there are also maps. At a single glance, the following map brings home one of the most horrific aspects of the war: the carpet bombing of Vietnam by the U.S. Each pinprick symbolizes the dropping of ordnance between 1965 and 1975. A few things strike the unprepared observer. First, the map does more than merely point out where those bombs fell. By the sheer mass of dots swarming across the map, in many places congealing into broad swathes of sheer black, the effect is almost as if we’re observing some kind of medical malignancy, perhaps an X-ray of a limb being destroyed by cancer. Second, the carpet of bombs doesn’t quite cover the entire country. Large parts of North Vietnam are relatively bomb-free, possibly because of limited bomber range, effective anti-aircraft deterrent, or both. In those lightly-bombed areas, it is easier to recognize the roads and paths that were the target of much of the raids, also further south. Smaller sections of the South are also relatively bomb-free. Third, the bombing didn’t stop at the borders of Vietnam. America’s enemies found alternative routes and hideouts outside the country, and America’s bombs went to find them there. Large parts of Laos and Cambodia, Vietnam’s neighbors to the west, were also bombed to smithereens.

Bombing Vietnam — and its neighbors

Then, if you look closely, you see some bombs were dropped well outside the main theater of operations: quite a few on Thailand, a single drop on Myanmar and more than a handful on China. Really? That seems rather unlikely, because it would have been rather dangerous. China was an ally of North Vietnam, but it was not in direct military conflict with the U.S. American bombs on China would have risked drawing in the Chinese, resulting in a much wider, much bloodier war. And finally, it seems the Americans also made an enemy of the ocean, because they dropped quite a bit of ordnance in the sea, including in two curiously triangular-shaped areas just off the coast of Thừa Thiên Huế province (whose borders are marked in yellow on the map). In the North, it may be assumed that the target was enemy shipping. Elsewhere, and considering the geometrical patterns of the areas of disposal, it may simply be that dropping non-delivered payloads in the sea was somehow easier (or less dangerous) than carrying the explosives back to base. The map above is taken from At the Heart of the Vietnam War, a monograph about Herbicides, Napalm and Bulldozers Against the A Lưới Mountains, published in 2016 in the Journal of Alpine Research. As the title suggests, the article’s main topic is the environmental degradation of this area, now in central Vietnam. The aim of the aerial sprayings of herbicide and bombings with napalm by the U.S. and South Vietnamese was not just to hit the enemy but to degrade their environment — to such an extent that they would find it harder to survive and would be easier to spot. The Viet Cong, for their part, used bulldozers to construct roads, in the process also seriously degrading the environment. As such, the article offers no further context to the map of bombings across Vietnam and its neighboring countries. It does offer a few other maps that, although more regional, illuminate certain aspects of the Vietnam War.

Photo-Source: bigthink.com

Tuy đã trải qua thời gian dài vùi sâu dưới lòng đất nhưng chúng vẫn cực kỳ nguy hiểm, có thể phát nổ và gây thiệt hại đến tính mạng, tài sản của nhân dân bất cứ lúc nào.

Dear editors, Biography of a bomb is aimed at highlighting the danger caused by unexploded bombs. Moreover, the most important aspect is that we work completely non profit, raising awerness about this topic is what drives us. We apologize if we make use of pictures in yours articles, but we need them to put a context in how findings are done. We will (and we always do) cite source and author of the picture. We thank you for your comprehension.