By Maja Adena, Ruben Enikolopov, Maria Petrova, Hans-Joachim Voth 19 November 2020

In conflicts, adversaries aim for victory by using both direct and indirect forces to break the enemy’s will to resist. During WWII, Allied forces used strategic bombing and radio propaganda to undermine German morale. This column compares German domestic resistance to the Nazi regime, based on treason trial records, with the monthly volume of bombing and the locations of BBC radio transmitters. Where radio reception was better and Allied air forces bombed more heavily, German domestic resistance was markedly more likely, despite the draconian punishments for even the mildest transgressions.

Is the word mightier than the sword? In most conflicts, adversaries aim for victory by both direct and indirect forces, undermining the enemy’s will to resist. ‘Shock and awe’ – impressive shows of strength – and propaganda can be used to rally one’s own side and to weaken the enemy’s morale. Rapid, easy victories often rely as much on military might as on destroying the enemy’s morale (Horne 2012, Van Creveld 2007). Herodotus tells us how the Persian king Xerxes I, invading Greece and finding his path blocked at Thermopylae, sent out envoys who threatened the defenders with massive volleys of arrows that would block the sun. Recent evidence from WWII suggests that radio could serve as an important means of coordinating Italian partisan attacks with Allied conventional forces (Gagliarducci et al. 2020). Nonetheless, how enemy morale can be broken is an open question. While there are numerous historical case studies, little systematic data exist on the use of tools used to undermine the enemy’s will or their effects (Beaven 1999, Gregor 2000, Jones et al. 2004, Briggs 1995). In a new paper, we examine this question using evidence from the most deadly conflict in world history, namely, WWII (Adena et al. 2020). Strategic bombing was a key part of the fighting. Allied air forces dropped conventional bombs with a destructive force equivalent to 230 atomic bombs between 1939 and 1945 (Overy 2014, Hastings 2013). Most of them hit German cities, causing 400,000 casualties. The strategic bomber offensive also absorbed significant resources, costing the UK 12% of GDP (and the US, 6%). Losses among Allied aircrew amounted to more than 80,000 dead (Overy 2014). In the run-up to WWII, military theorists, politicians, and journalists had generally expected air attacks to be a highly effective tool in breaking the will of the enemy. As Stanley Baldwin, UK prime minister, said in 1932, “the bomber will always get through” (Hastings 2011). The air war against Germany is generally regarded as a gigantic failure. John Kenneth Galbraith, who analysed its effects for the US military after 1945, concluded that it was “one of the greatest, perhaps the greatest, miscalculation of the war” (Overy 2014). After 1941, it quickly became clear that pinpoint attacks on industrial and military targets were impossible because of inadequate technology, poor weather, and vigorous German defence. In response, both British and US air forces switched to ‘city bombing’ – mass attacks against the civilian population (Keeney 1988). While the US paid lip service to the idea of precision bombing, de facto both UK and US bomber forces were used for terror attacks. The devastation wrought was unprecedented in history – millions of homes were destroyed, hundreds of thousands of civilian lives were lost, and in the centres of most larger German cities, few buildings remained undamaged. The commander of UK Bomber Command, Arthur Harris, confidently expected by 1944 that Germany would soon collapse because of his attacks (Hastings 2013), making an invasion of the continent unnecessary. The German side did not think very differently; after the firebombing of Hamburg in the summer of 1943, Albert Speer, Minister for Armament under Hitler, thought that “six more Hamburgs, [and] Germany will be finished.” WWII also saw, for the first time in history, the widespread use of radio propaganda. The Germans paid Frenchmen and British broadcasters – like the infamous ‘Lord Haw-Haw’ (William Joyce) – to spread a mixture of falsehoods and information. The BBC signed up numerous German émigrés for its programmes. Using high-powered transmitters in England to reach most of Germany, the BBC combined entertainment with news and political commentary. Particularly powerful was the BBC’s use of honest reporting, admitting British defeats before German radio had even reported its own side’s successes (Briggs 1995). As the war news worsened for the Axis, many Germans tuned in to the BBC to learn how the war was going. According to the best estimates, up to 15 million Germans listened in to the BBC. The air offensive failed twofold, according to the established view. While Germany was being bombed ever more intensively as the war progressed, armament production continued to surge until almost the end – the peak of production for most weapons systems was in late 1944 (Overy 2014, Tooze 2008). Second, no large-scale resistance movement against the Nazi regime sprang up in Germany; there was no mutiny of sailors and soldiers nor a rebellion by the general public, as there had been in 1918.

Range, resistance, and resignation

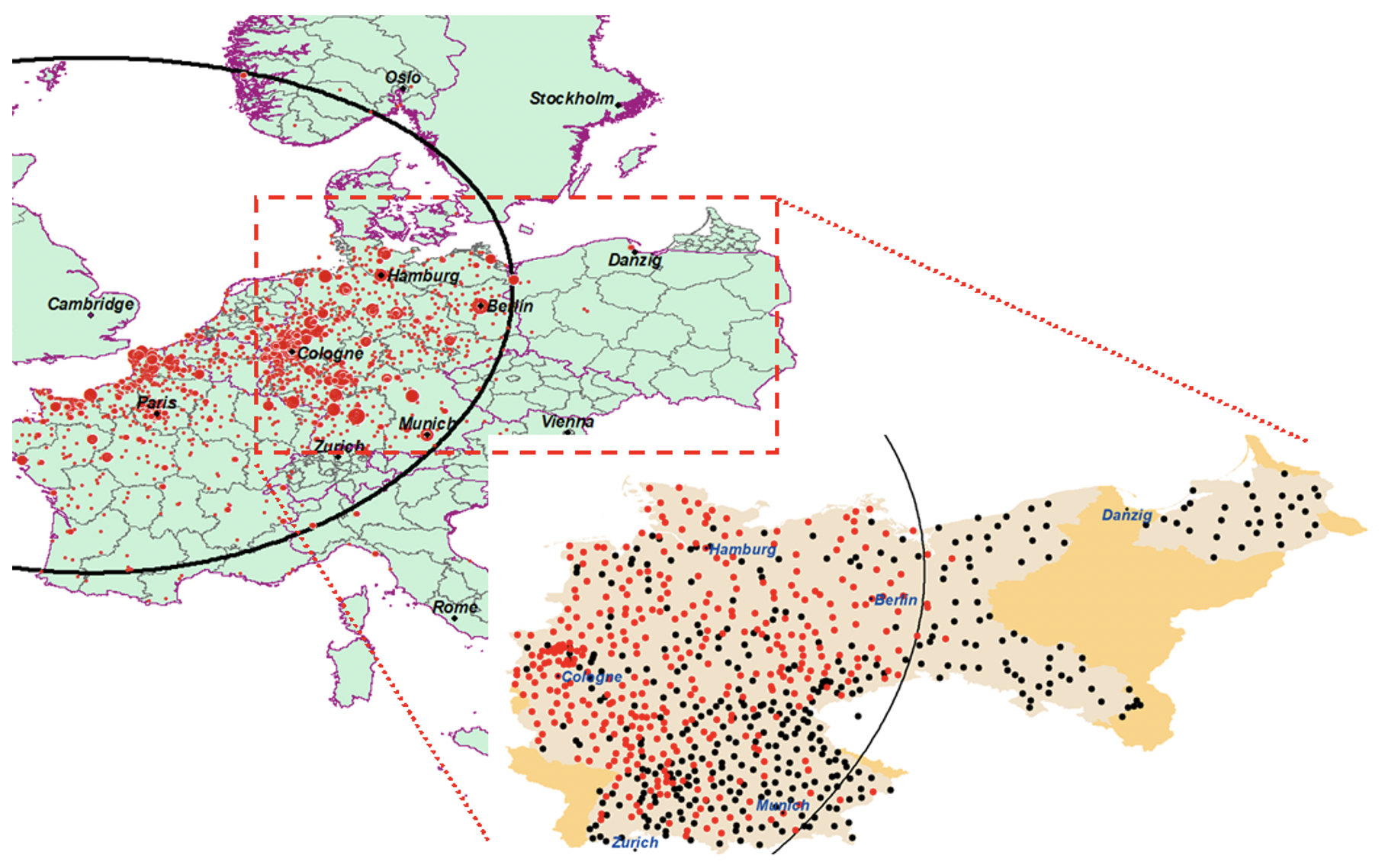

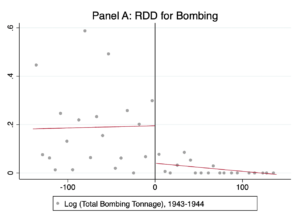

To examine the effects of both bombing and propaganda, we collect data on domestic resistance in Germany from treason trials. We find that both bombing and propaganda were effective in boosting opposition. While there was never unrest on the scale of 1918, this nonetheless demonstrates that the basic mechanism worked: bombing and propaganda were effective in undermining support for the Nazi regime. One reason why the war did not end in revolution is that the Nazi regime cracked down even harder on all forms of domestic opposition after the war began, fearing a repeat of 1918 (Evans 2009). From 1943, it centralised the jurisdiction over all resistance cases at the People’s Court, carefully staffed with Nazi judges (Geerling and Magee 2017, Geerling et al. 2015). We use court records of 640 cases, involving 2,000 defendants, to carefully document when resistance activity began and combine this information with data on the location of BBC radio transmitters as well as the monthly volume of bombing in 1,024 locations. We find that where radio reception was better, and Allied air forces bombed more heavily, domestic resistance was markedly more likely – despite the draconian punishments in place for even the mildest transgressions, like telling jokes. Places easily bombed were closer to US bomber bases in the UK. The further east a German city was, the harder it was to reach; some cities were out of range for the main long-range bomber of the US Army Air Force, the B-17. We can use this simple fact to get a sense of how much bombing and domestic resistance correlated. Of the over 1,000 locations in our sample, 85% were within the range of the B-17; 53% of these were bombed during the war. In contrast, of locations out of range, only 9% were bombed – either by longer-range British planes like the Lancaster bomber or by B-17s with markedly reduced loads, operating at the extreme outer limit of their range.Domestic opposition activity overwhelmingly took place in towns and cities within B-17 range – 94% of all resistance occurred in locations easily reached by UK-based bombers. Figure 1 illustrates the basic logic, showing the effective combat range of B-17s from their bases in East Anglia and the pattern of bombing in Europe and Germany in particular. We look for discontinuities in the spatial pattern of bombing and resistance. Figure 2 shows that once the effective range of US bombers was reached, both bomb tonnage and resistance frequency fell sharply and discontinuously.

Figure 1 Allied bombing and effective range of B-17 bombers

Notes: In the upper map, the size of dots corresponds to the overall volume of bombs (tonnage dropped). In the lower map, black dots indicate unbombed towns and cities (by December 1944). The black line indicates the effective combat range of B-17 bombers by 1943.

Figure 2 Bombing and resistance: Regression discontinuity results

Note: The figure shows the log of bomb tonnage dropped on German towns and cities (Panel A) and resistance (Panel B) as a function of distance to the maximum operational range of B-17 bombers, normalised to 0. Negative values indicate that a location is within range. Distance is given in kilometres.

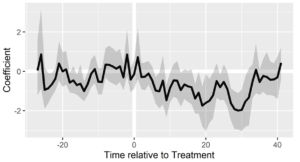

To rule out omitted variable biases – such as a targeting of high-value military targets, leading to incidental attacks on cities – we exploit the variation in bombing volume caused by the weather. We collect daily data on windspeeds over Germany for every day of WWII. High winds reduced the effective range of bombers, making it harder to reach targets further east. We first show that same-day wind negatively predicts bombing volume for targets far from the UK (where UK and US bombers were mainly based). At the same time, with reduced operational ranges due to the wind, Allied air forces switched their bombing to closer towns and cities. We then aggregate wind-predicted bombing to the monthly level and examine its predictive power for the start of resistance activities. We find a strong, positive effect of bombing on resistance. Doubling bombing tonnage increased the number of new resistance cases by an average of 4.8% to 19%, depending on the estimation method used. Radio magnified this effect. While not particularly effective on its own, it boosted the effect of bombing on morale. Where both radio reception was excellent and bombing intensive, many more Germans chose to resist the Nazi regime – often at the cost of their lives. Allied bombing also undermined the morale of German soldiers. From 1943 onwards, officers regularly reported that their men came back depressed from home leave; emergency postcards sent immediately from bombed-out family members in attacked cities to men fighting at the front reassured them of the survival of their dearest but also revealed the scale of disaster befalling the Reich (Hastings 1981). We use detailed records on the performance of 352 German fighter aces to assess the demoralising effect of bombing, building on data collected by Ager et al. (2017). As soon as a pilot’s hometown is bombed, we find a strong decline in performance – and the effect grows with every additional attack. While these pilots typically destroyed around two Allied aircraft per month before their hometown was bombed, this number went down by 0.5 aircraft on average per month thereafter. Figure 3 shows how the effect grows over time and remains significant for around 20 months.

Figure 3 Fighter pilots’ performance after hometown bombing

Note: The figure shows the ATT for bombing of a pilot’s hometown, with monthly victory count as the dependent variable. Time of hometown bombing is normalised to zero. The coefficient is derived from 1,000 bootstrap iterations of the synthetic control procedure described in Xu (2017). Treatment occurs at time=0. The coefficient is equivalent to the change in the number of enemy aircraft shot down per month.

Conclusions

Is violence against civilian populations ever ‘the answer’? Or are, for example, drone strikes on suspected terrorist camps counterproductive, resulting in the recruitment of yet more terrorists (Shah 2018, Kattelman 2020, Piazza and Choi 2018)? In a recent paper, we examine the effect of Allied bombing on domestic resistance against the Nazi regime in WWII Germany (Adena et al. 2020). Despite the extraordinary effectiveness of the Gestapo – the German secret police – and the propaganda prowess of the Nazi regime (Evans 2009), we find that a combination of Allied radio propaganda and military force helped to create resistance on the ground. The more German cities turned into rubble at the hands of Allied bomber crews, and the more easily Germans could listen to the BBC, the clearer it became to them that the war was lost – and the more likely active acts of domestic resistance became (USSBS 1945). An important synergy between radio and bombing also suggests that the same level of resistance could have been produced by better radio transmission and fewer bombs: We estimate that an increase of one standard deviation in radio signal strength would have had the same effect as a 25% increase in bombing. In other words, a government’s failure to protect its own population undermined support in Germany during WWII – as it did in Vietnam (Dell and Querubin 2018). The effect of bombing did not stop with the civilian population. We examine the performance of fighter pilots, whose skill and commitment were essential for success (Ager et al. 2017). While it is theoretically possible that strong supporters of the regime might have ‘closed ranks’ and supported it even more in the face of adversity, that is not what we find. Whenever the hometown of a fighter ace was bombed, his performance suffered – immediately, and for many months thereafter. Recent research has already reassessed the military value of the Allied air campaign, arguing for much greater benefits (O’Brien 2015). Our research suggests that strategic bombing was not ‘the greatest mistake’ of the war. While no wave of popular unrest swept the Nazi government from power, the basic mechanism – the destruction of cities demonstrating that Germany could not win, thus sapping morale – worked as intended. Hermann Goering himself, the head of the Luftwaffe, told his entourage in 1944 that the war was lost when he saw the first US Army Air Force B-17 bombers over Berlin accompanied by long-range fighter escorts (Hastings 2013, Evans 2009). Both the morale of top performers in the German armed forces as well as of civilians back home were effectively undermined by the hail of bombs that hit Germany from 1942 onwards. This does not mean that terror bombing was morally justified or that the same resources could not have been used elsewhere, perhaps to greater effect; but it casts doubt on the widespread belief that external pressure will always backfire, galvanising support for the enemy (Kattelman 2020).

References

Adena, M, R Enikolopov, M Petrova and H-J Voth (2020), “Bombs, broadcasts and resistance: Allied intervention and domestic opposition to the Nazi regime during World War II”, CEPR Discussion Paper DP15292.

Ager, P, L Bursztyn and H-J Voth (2017), “Killer incentives: Status competition and pilot performance during World War II”, CEPR Discussion Paper 11751.

Beaven, B, and J Griffiths (1999), “The Blitz, civilian morale and the city: Mass-observation and working-class culture in Britain, 1940–41”, Urban History 26(1): 71–88.

Briggs, A (1995), The war of words: The history of broadcasting in the United Kingdom: Volume III, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dell, M, and P Querubin (2018), “Nation building through foreign intervention: Evidence from discontinuities in military strategies”, Quarterly Journal Economics 133: 701–64.

Evans, R J (2009), The Third Reich at war, London: Penguin.

Gagliarducci, S, M G Onorato, F Sobbrio and G Tabellini (2020), “War of the waves: Radio and resistance during World War II”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12: 1–38.

Geerling, W, and G Magee (2017), Quantifying resistance: Political crime and the People’s Court in Nazi Germany, Studies in Economic History, Singapore: Springer.

Geerling, W, G B Magee and R Brooks (2015), “Cooperation, defection and resistance in Nazi Germany”, Explorations in Economic History 58: 125–39.

Gregor, N (2000), “A Schicksalsgemeinschaft? Allied bombing, civilian morale, and social dissolution in Nuremberg, 1942-1945”, The Historical Journal 43(4): 1051–70.

Hastings, M (1981), Das Reich: The march of the 2nd SS Panzer Division through France, Michael Joseph.

Hastings, M (2011), Inferno: The world at war, 1939-1945, Vintage.

Hastings, M (2013), Bomber Command, Zenith Press.

Horne, A (2012), To lose a battle: France 1940, Pan Macmillan.

Jones, E, R Woolven, B Durodié and S Wessely (2004), “Civilian morale during the Second World War: Responses to air raids re-examined”, Social History of Medicine 17: 463–79.

Kattelman, K T (2020), “Assessing success of the global war on terror: Terrorist attack frequency and the backlash effect”, Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict 13: 67–86.

Keeney, D (1988), The Pointblank Directive, Osprey.

O’Brien, P P (2015), How the war was won, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Overy, R (2014), The bombers and the bombed: Allied air war over Europe 1940–1945, Penguin.

Piazza, J A, and S-W Choi (2018), “International military interventions and transnational terrorist backlash”, International Studies Quarterly 62: 686–95.

Shah, A (2018), “Do US drone strikes cause blowback? Evidence from Pakistan and beyond”, International Security 42: 47–84.

Tooze, A (2008), The wages of destruction: the making and breaking of the Nazi economy, Penguin.

USSBS (1945), “The US strategic bombing survey: The effects of strategic bombing on the German war economy”, Overall Economic Effects Division.

Van Creveld, M (2007), Fighting power: German and US Army performance, 1939-1945, Westport CT: Greenwood Press.

Foto-Fonte: https://voxeu.org/article/how-allied-bombing-and-propaganda-undermined-german-morale-during-wwii